All of us can relate to what it’s like to feel stressed—it’s a natural and inevitable part of life. Although painful and difficult, many stressors are temporary, and we typically can bounce back with few lasting effects. However, when adversities arise unexpectedly, are extreme, are long-lasting, and/or far-reaching, it’s understandable for us to feel the physical and emotional effects.

In distressed moments, we often experience prolonged anxiety and depressed mood. Prolonged anxiety is characterized by almost constant worry and a sense of apprehension that is difficult to control. Virtually everyone can describe personal examples of times they have felt anxious and worried. It’s a natural part of being human. Anxiety is an emotion associated with a sense of future danger, misfortune, and dread. This means that we can become anxious about things that may or may not actually be harmful or that might never come to be. Nonetheless, anxiety helps us survive by signaling that an outcome is important to us and mobilizing us to act to prevent a possible negative event from happening. When depressed mood is present, it is often accompanied by low energy, sleep or appetite disturbance, loss of interest in things that one once found pleasurable, difficulties concentrating, and a sense of despondency in their lives. Sadness is a common emotion in depression, which acknowledges an important loss or an unreachable goal, allowing for disengagement.

It’s important to understand that humans do not simply have emotions that pop up and then subside. Instead, emotions work more like a feedback loop. When we notice the arising of an emotion, we automatically start looking for the triggers outside ourselves or even inside our minds for what has led to this emotion in this moment, so that we can respond to it. Often though, our responses are partially or mostly in our minds as we decide how best to make sense of- and seek control over a potential threat or loss, or even a pleasurable or rewarding opportunity. This way of responding to emotions is natural and healthy most of the time.

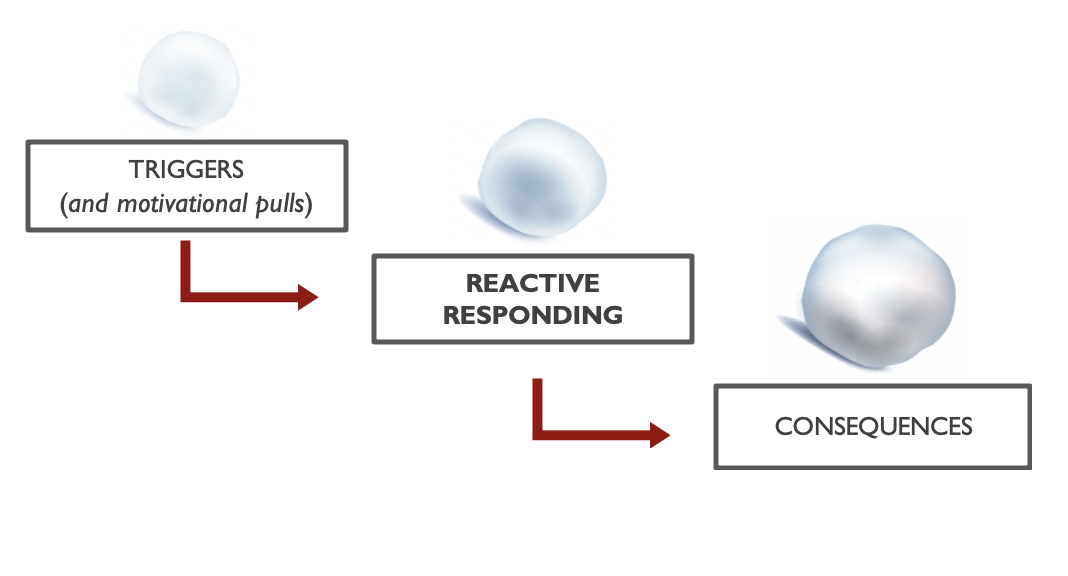

However, what we call “reactive responding” occurs in distressing moments that provoke a jumble of intense negative emotions, where our responses often prioritize escaping, avoiding, dampening, or withdrawing from the intensity of the emotional experience even if it interferes with what is important to our happiness, and obligations to family, relationships, work or school. Distress leads us to talk to ourselves in ways that we hope might reduce the distress in the short-term, but in actuality worsens and prolongs our suffering. In particular, worrying often helps in the short term to create the illusion that one can control anxiety by reducing uncertainty. Rumination can seem like a form of problem-solving as we pour over possible solutions or responses to something that did not go well. Self-criticism is common in response to having gotten emotional in the first place; or perhaps in response to our lack of assertiveness or dependency upon others.

We can also try to dampen our emotional experience and gain control and safety with our behaviors. For instance, we may ask confidants or loved ones for reassurance in troubling times when we feel unable to tolerate our emotional lives and hope that others will instrumentally support us in this time of need. Distress can also lead us to reduce contact, to isolate, or to avoid persons, places, or activities when there appears to be no possible solution to an actual or perceived problem. Finally, when we feel distressed we might be more prone to compulsive repetitive behaviors, including over- or under-eating, drinking, smoking, or drug use, or engage in self-destructive behavior.

A big part of ERT is helping you break the cycle of reactive responding when you feel distressed and an important first step is noticing where you are in this negative feedback loop. In ERT, we often ask patients to imagine a dirty snowball, which probably has rolled down a hill, and in the process, picked up dirt and grime and twigs and leaves, and has formed a hard icy shell. It didn’t start that way! At the top of the hill, right after the snowfall, the snow started out pristine and fluffy because pure snow is just a frozen form of water, with nothing added. Our initial emotional and motivational reactions are much like a ball of this pristine and pure snow. But, when we are feeling distressed, we may become preoccupied with efforts to escape or de-intensify our emotional experience, which may be symbolized by our pristine snowball rolling down the hill and becoming dirty and hardened along the way. Reactive responding, in the short run, might help us reduce the intensity of difficult negative emotions, but like a dirty and icy snowball, all it really accomplishes is closing us off from the original emotions and the motivational pulls that would serve to guide us in helpful ways

It’s for these reasons that now, over the next 10 sessions, and ideally, going forward in your life, we encourage you to pay attention to your emotions, all of your emotions, (even the difficult ones) so that you can find helpful and effective ways to respond that reduce the burden and intensity of your distress. ERT has ways to help you.

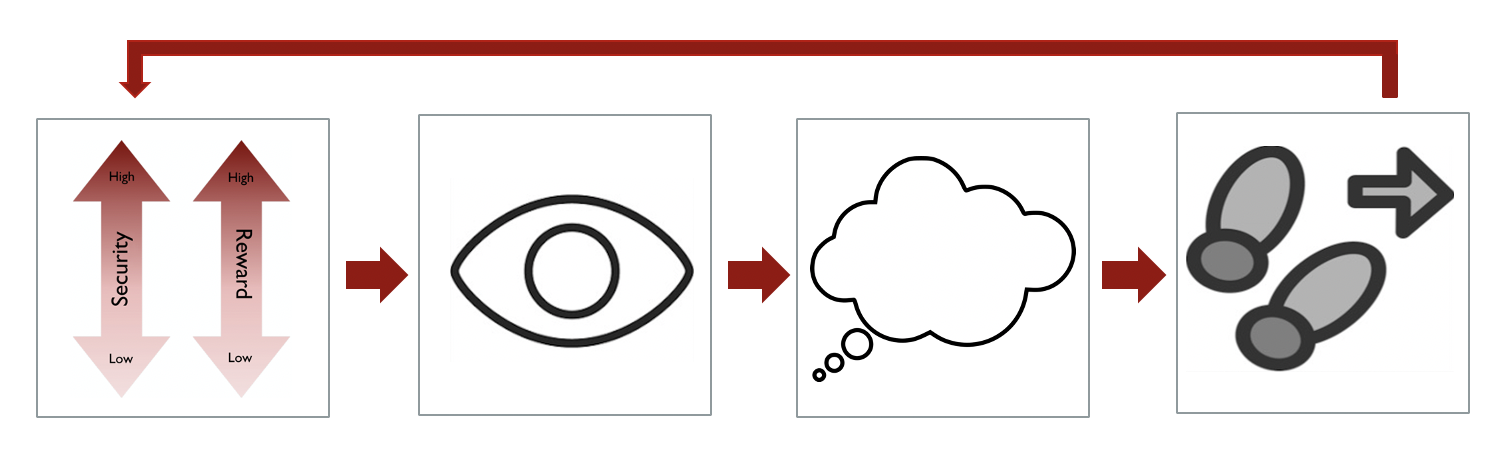

When we are in distressed moments, our fears, our losses, and our desires or difficulty obtaining them become very salient. The overwhelming impact and burden of stressful events make us aware of how much we feel driven to make everyday decisions by simultaneously weighing how much threat we are faced with versus how much opportunity we are missing out on for ourselves or for our families. However, even in calmer times, nearly every decision we make in our daily life reflects a balance of threat and reward.

To effectively manage these emotional moments, we focus our attention and rely on our senses to receive information about a situation to assess how much personally relevant and rewarding opportunities are present but also, how much risk and effort stands in our way. All the while, our brain is working like a calculator to help us weigh the possible benefits and rewards in the face of risk and effort so that we choose the best course of action to take in that moment. But, particularly in these times of distress, these feelings and urges can feel especially intense and confusing, which can constrain our attention and make us not want to stay in contact with difficult feelings and images, undermining our ability to know what actions to take.

In addition, there are times when the information about a particular situation is not available or is possibly contradictory or ambiguous. When environmental cues for threat and reward are subtle or ambiguous or when we are otherwise inattentive or distracted, our minds naturally “fill in the blanks” allowing us to remember how we handled past situations or imagining ourselves into future situations, to help us determine the best course of action in a given moment. But, distressing moments, especially during challenging experiences, can increase negative self-talk including worry, rumination, and self-criticism. These thoughts often revolve around seeing ourselves stuck, held back, or obligated to confront possible future threats or losses instead of focusing on what might be more personally relevant like our work or school, our family and relationships, or our community.

Finally, when our minds are filled with these distressing thoughts, cues of threat and loss may be amplified and overshadow our ability to notice the availability of pleasurable or rewarding opportunities or diminish our confidence in our ability to obtain them, or both. We are more easily triggered by something that reminds us of our distress. We look for ways to gain a greater sense of control, or to reduce a sense of threat, danger, or loss in hopes of pushing away, or reducing the intensity of the emotional experience. We are more likely to eat poorly, drink or smoke more, avoid things that take energy, or seek reassurance about ourselves from confidants or loved ones. Eventually, self-care becomes more difficult.